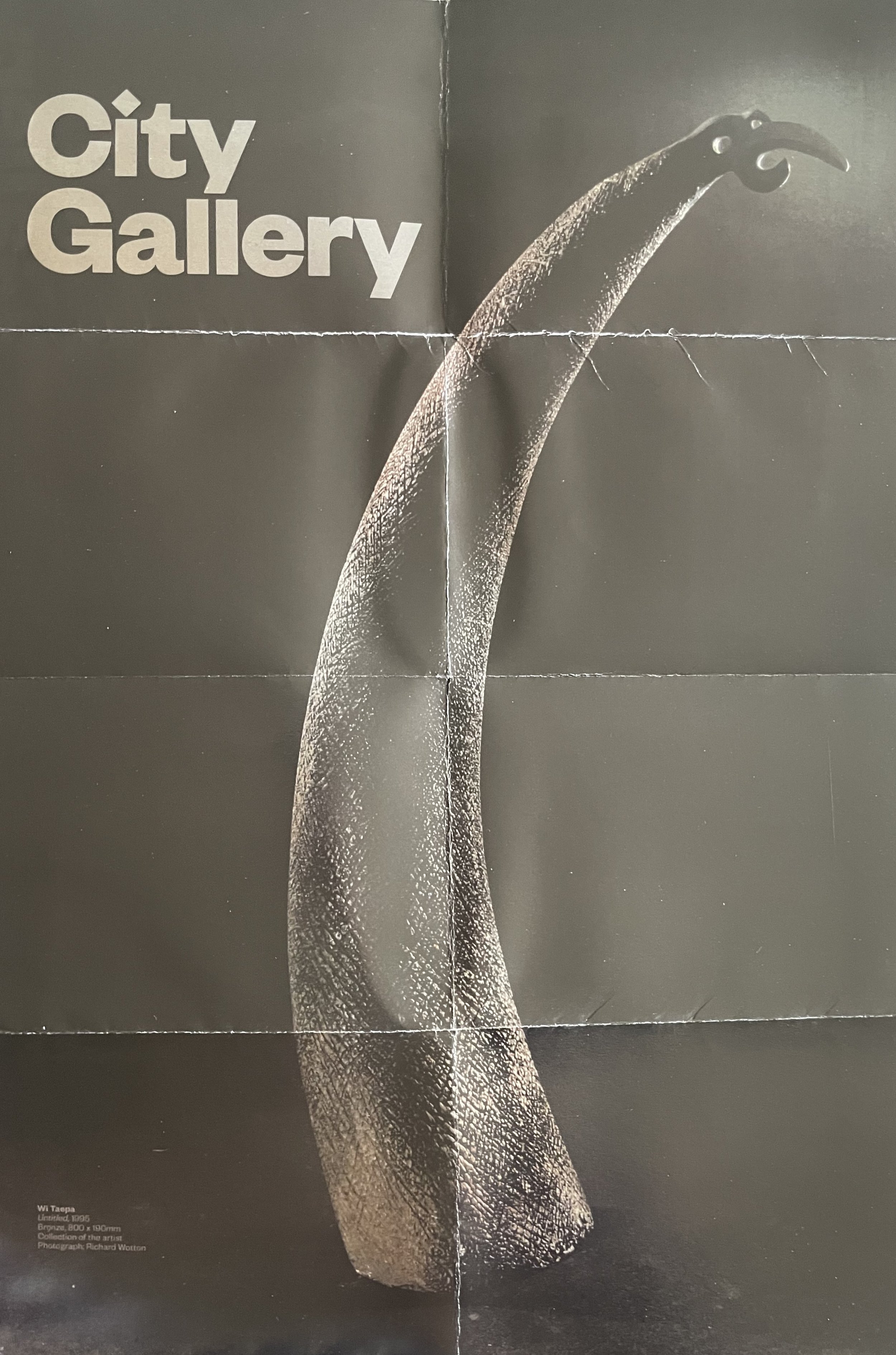

Wi Taepa

City Gallery Wellington | Whare Toi

Deane Gallery, 23 June–5 August 2012

Wi Taepa (Ngāti Pikiao, Te-Roro-o-Te-Rangi, Te Arawa, Te Āti Awa) is a ceramicist. His 2012 series addresses physical and cultural survival during a time in his life where life threatening ailments from his experiences in the Vietnam War had begun to have increasingly severe implications.

Seven sculptures run down the centre of the gallery, symbolising a waka (canoe). The sequence begins with a manaia (a bird-like figure), representing intangible energies, such as māuri and mana. A waka pito (umbilical-cord box), celebrating new life, sits near a waka kōiwi (burial chest), representing death. There are vessels: a hue (gourd), a kumete (food bowl), and a hīnaki (eel trap).

The works embody Māori collective struggles as well as Taepa’s personal experience of the Vietnam War and the continuing affects of post-traumatic stress disorder. They are the reflections of an artist, soldier, father, and environmentalist.

The following text is taken from the exhibition catalogue that accompanied the self-titled exhibition Wi Taepa:

Wi Taepa

By Reuben Friend

In te ao Māori (Māori worldview), uku (clay) is more than an artistic material, it is a blood relative. Working with it requires an understanding of the genealogical links between humanity and Papatūānuku (Mother Earth). It is a powerful medium imbued with mauri and mana atua, godly power and prestige. Negotiating this relationship is a constant and defining feature of Māori ceramics.

The sculptures in Wi Taepa's self-titled solo exhibition traverse this terrain between cultural and personal narratives. His clay sculptures reference Māori creation stories to deal with recent experiences in his personal life that have left him considering his own mortality. In dealing with these issues Tapa's works take us back to the beginning of time, exploring the whakapapa, heritage, of uku and the creation of the first human.

In the beginning there was Te Kore, an infinite yet fertile nothingness. From Te Kore came lo-matua-kore, the parentless creator, and from him flowed the waters of life. Out of these waters came the oceans and from the oceans rose Papatūānuku, the earth, and Ranginui, the sky. Ranginui and Papatūānuku had seventy male children who became the gods of the earth, sea and sky. It was the responsibility of Tane, the god of men, to bring life into the world. He courted the mareikura (female supernatural beings) in the heavens and on earth and together they created numerous offspring.

Putoto, the god of magma, came from Tane's union with the mountain Hine-tu-pari-maunga. Putoto joined with Parawhenua, god of rain and deluge, and gave birth to various types of soil, sand and stone. Among them was Hine-uku-rangi, the goddess of clay' Tane wanted to create a human likeness of himself but could not find a human mareikura. He sought advice from the Apa-kura, the denizens of the heavens, and was told to create a woman from the fertile soil found at Kurawaka (sacred vessel). There Tane moulded the likeness of a woman from the soil that had been stained by the blood of Papatuanuku. lo-matua-kore passed down to Tone the breath of life and he blew this into the clay maiden's nostrils, awakening her with an almighty tihei mauri ora, the sneeze of life. Tāne named her Hine-ahu-one, woman born of earth. From them came the first naturally born person, Hine-titama, the dawn maiden. Unfortunately, with the first birth also came the first death, and Hine-titama returned to the earth to dwell in Rarohenga, the land of the dead. There she changed her name to Hine-nui-te-po, the great maiden of the night, and became the guardian of the afterlife.

In Rarohenga she married Whakaru-au-moko, the deity of earthquakes and their twenty-one children were reborn into the world of the living in the form of volcanoes and lava. Throughout this whakapapa, relationships between people and the earth are constantly reinforced: mountains give birth to clay, clay gives birth to human life, from life comes death and from death comes renewed life. These stories form an allegory of the cycle of birth, life, death and afterlife as perceived in te ao Māori. Such beliefs form a cultural anchor, a point of reassurance that in life and death we belong to something bigger than ourselves.

Using culture to reconcile one's own mortality is something that Taepa is acutely aware of. From 1970 to 1972 Taepa fought in the New Zealand Army in the Vietnam War. Part of an elite fighting contingent nicknamed the Grey Ghosts, he and his company gained a name for themselves for their deft ability to enter enemy territory under stealth. Taepa recalls searching for underground bunkers and finding entire hospitals hidden in tunnels buried deep beneath earth and vegetation. Here Taepa encountered the ancient stories of earth, life and death in vividly real terms.

For those New Zealand veterans who returned home alive, the war has had long-lasting psychological effects that continue to haunt them today. Taepa recalls spending days completely drenched in chemical toxins as planes sprayed Agent Orange to thin the dense bush - an experience that he continues to suffer from both physically and emotionally. Taepa says that most Vietnam veterans have yet to see any assistance from the government to help deal with post-traumatic stress disorder or illnesses related to dioxin poisoning. While Taepa has historically shied away from talking about these matters publicly, recent health disorders associated with his time in Vietnam have prompted him to share his experiences.

On the rear wall of the installation is a black and white projection depicting Taepa and five of his comrades in Vietnam. Taepa has purposefully blurred the image to make the figures grey and indistinguishable. Presented in this ghost-like manner, the image is a memorial to those soldiers in the photo who have since passed.

Amongst the calamity of war however, brief moments of beauty were found in the tradition and culture of the people. Tapa recalls visiting markets in Vietnam and being impressed by the arts and crafts, in particular the patterning on the weaving and ceramics.

This experience sparked a creative germ and inspired him to learn more about Māori art and culture. On his return to New Zealand Taepa taught Māori arts and crafts to prison inmates and troubled youth. For Taepa and his students, art and culture became a form of therapy, a creative outlet that allowed them to communicate ideas and work through life's issues.

In this exhibition seven sculptural forms run down the centre of the gallery, symbolising a waka. Each of the forms represent different aspects of life, death and rebirth. The sequence begins with a manaia, a bird-like figure that commonly represents intangible energies such as māuri and mana. Within the sequence a waka pito (umbilical cord box), celebrating new life, sits near a waka kōiwi (burial chest), representing death.

Here also are food vessels such as a hue (gourd) kumete (food bowl) and a hinaki (eel trap). Customarily tapu (sacred restrictions) requires food vessels to be separated from funerary objects, however these objects are ceremonial offerings not intended to receive kai (food) but rather placed here to represent the stages of birth, living, death and the afterlife.

Taepa relates these forms to the great celestial waka of Tamarereti - the personified constellations of the Milky Way. In a popular version of this story the stars are said to be the glowing, bodiless eyes of the gods. Tamarereti collected these eyes in calabashes which he tied to his waka. Sailing into the night sky he began placing key navigational stars into the heavens but capsized his waka before he could finish. The trail of stars can be seen scattered across the Milky Way. Taepa's manaia sculpture forms the tauihu (prow) of Tamarereti's waka This is the constellation Scorpius, referred to in Māori cosmology as Manaia ki te Rangi (Manaia in the sky) or Te Waka o Mairerangi (the waka of Mairerangi).5 Taepa's hue and other food-storing vessels symbolise Tamarereti's calabashes. Tautoru (Orion's Belt) forms the taurapa (stern) of the waka and is embodied at the rear of the installation in the waka koiwi. The small figures on the rear wall represent the seven stars of Matariki (Pleiades). The appearance of Matariki, literally meaning eyes of the gods', in the sky in early in June signals the end of winter and the beginning of the Māori New Year.

It is a time for remembering those who have passed while planning for the future— an event of particular importance to Taepa after a year beset by health issues.

Running concurrently to this exhibition, Taepa's works feature in a Matariki exhibition at the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, Wellington. His works will be on display with many of his peers, in particular members of Ngã Kaihanga Uku, the national Māori clay workers collective— a group Taepa helped found over a quarter decade ago. Their work has uncovered links between Māori artistic traditions and the ancient Lapita pottery of Micronesia and Melanesia. Together they have fostered a new generation of Māori clay sculptors who carry the mantle of uku into the future.

Taepa's works are layered with an abundance of rich cultural and personal tales. Ultimately, they are works about survival. The survival of people, culture and the environment. They are about human activity and sustaining a healthy connection to the earth. Like the story of Hine-nui-te-põ, the works deal with the joys, tragedies and cycles of life, presenting a solid cultural framework through which to navigate one's way through life.

S. Percy Smith, The Lore of the Whare Wananga (translated from the writings of H. T. Whatahoro taken from the teachings of Te Matorohanga and Nepia Pohuhu), New Plymouth, 1913, p. 79-149

Ibid.

The endangered New Zealand kokako is often referred to as a

Grey Ghost because of its tendency to go quiet when humans are spotted. There is also an elite United States air force squadron named the Grey Ghosts who also fought in the Vietnam War.This is a generalised account. Details vary from region to region.

Polynesian star constellations are referred to by different names at certain times of the year to relay different sets of information, hence the waka of Tamarereti can be seen in New Zealand in June but is not referred to as such until November.

Wi Taepa (born Wellington, 1946) is of Ngāti Whakaue, Te-Roro-o-Te-Rangi, Te Arawa and Te Atiawa iwi. In 1992 he gained a Certificate in Craft Design from Whitireia Polytechnic, Wellington and subsequently taught clay sculpture at Whitireia Polytechnic, Whanganui Polytechnic and Te Whare Wananga o Awanuiārangi in Whakatane.

Tapa has exhibited widely in New Zealand and internationally, having works in private collections in Africa, England, Europe, the United States of America and Samoa. His works are held in public collections throughout New Zealand including the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington; Pataka Museum of Arts and Cultures, Porirua and The Dowse Art Museum, Lower Hutt.